Oh, dear. A couple of my colleagues were involved in a fairly contentious exchange over the meaning of Texas patriotism on this blog last week. As an historian of the Old South, albeit with no particular expertise in Texas, I feel I ought to make a contribution. For the record, I grew up in upstate New York and loved my beautiful “North Country,” but I was never asked to pledge my allegiance to the Empire State.

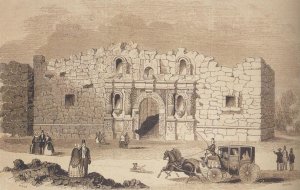

I have lived in Texas since 2008 and although the call to state patriotism is still strange to me, I understand something of the “mystique” of Texas. The land itself, with its wide-open spaces, nurtures a sense of independence and adventure. Texas author John Howard Griffin, writing of the Llano Estacado region, called it the “land of the high sky.” During my first full summer here I took a vacation in San Antonio and visited the Alamo daily. I came away the proud owner of a mug with an image of the Alamo, its distinctive round-topped façade silhouetted against a brilliant evening sky.

But would I pledge allegiance to my current home state? What would that mean? It would be an act of appreciation, as a colleague has suggested, but a pledge is more than a thank you note. It is a real commitment.

What troubles me is that in the romance of Texas, with its celebration of freedom, the contradictory elements are swept behind a curtain. The Americans settlers who arrived in the 1820s and 1830s brought their racial and religious assumptions with them, so that historian Randolph B. Campbell has described the Texas of this period as a “battlefield of conflicting cultures.” Many of the freedom-loving American settlers brought their slaves with them, and some became wealthy by dint of the hard labor of others as well as their own. When Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, the Anglo-Texans, or Texians, resisted to the point where President Guerrero felt obliged to declare Texas exempt from the decree. Another historian, David Montejano, has described the widespread hostility of Texians toward Mexican Texans, or Tejanos, after the Texas Revolution. Prominent Tejanos were driven off their property and entire communities were expelled from their towns. It made little difference that many of these Tejanos had fought on the side of Texas against the Santa Anna dictatorship. Even Juan Seguín, hero of the Texas Revolution, fled to Mexico in the face of death threats against him and his family.

On the eve of the Civil War, 30% of the Texas population was enslaved and 28% of Texas families owned slaves. Support for secession was closely related to rates of slave ownership and Texas was the last of the seven Deep South states to secede from the Union in the winter of 1860-61. In the decades after the Civil War as well, Texas generally adhered to the pattern of the Deep South in the imposition of racial segregation and in racial violence. Of the 329 men lynched in Texas between 1890 and 1920, 81% were black. Decades later, John Howard Griffin, whom I quoted above, was lynched in effigy in his hometown of Mansfield in retaliation for having published Black Like Me, an exposé of white racism in the Deep South in 1959. Like Seguín, he felt obliged for the safety of his family to flee the great state of Texas and find refuge in Mexico.

There are aspects of present-day Texas that leave me cold. I’ve never cared to celebrate guns. At best, they’re a grim necessity. Nor can I rejoice that my state leads the nation in executions and ranks near the bottom in the proportion of children without health insurance. Such statistics do point to a certain harshness in Texas’ political culture. My faith in “self-reliance” is qualified by the fact that the playing field is not level. Some people are genuinely disabled, some people are bereft of family and community. For them, no matter how hard they work, material success will come harder, if it comes at all.

And yet . . . the romance of Texas is there still, and I think the underlying yearning is valid. It points to our desire to believe in something noble, and pure, and beautiful. It was surely this desire that prompted the U.S. Army in 1850 to repair the crumbling shrine of the Alamo and add the memorable curving façade by which we recognize it today. The problem is that when I “remember the Alamo” this graceful curve is what I visualize, even knowing that it was not there when the Texian and Tejano defenders fought and died. In the same way, I struggle to balance the beautiful curves of the Texas romance with an historical reality that is as broken and ragged here as it is anywhere else.

To return to my own question, can I pledge allegiance to Texas? I can obey its laws, admire its beauty, appreciate its advantages, and value all of the cultures that have found a home in here. As a Christian, however, I have it on good authority that my true citizenship is in the Kingdom of Heaven. All of my other loyalties are contingent on their conformity to the laws of that country. And so I can love Texas and, I suppose, pledge my conditional allegiance. In any case, it wouldn’t hurt me to memorize the state pledge.

There. I memorized it.

7 responses to “The Romance of Texas”

Nicely done!

Some of those things you mentioned (slavery and racism) seem to be quickly forgotten. I’ve lived in Texas almost my whole life, and haven’t associated being a Texan with them. Of course, I’m young and there are a good many things I did not experience, yet I seem to think of being a Texan as freedom, not oppression. Interesting how things have changed.

That’s the great thing about studying history – you can be centuries older in your understanding than in your chronological age. Things are much better today, of course, but I’m afraid racism is not completely a thing of the past in Texas or anywhere in the States. Some of my students, who are about your age, have told me some distressing stories about their personal experiences with racism.

Awesome……..Just Awesome Share.I love it.Looking forward for more.Alex,Thanks.

[…] The Romance of Texas (reflectionandchoice.org) […]

If your allegiance is not to your country AND your state then why are you living in that state. It doesn’t matter which state. To me if you live in Texas and you’re just here for the money, then make your living, retire then go back to where you came from and do not return. I wasn’t born here, but I’ve been here most of my life. I will be burried here. I love this state. I started my journey through Texas in Stratford in the panhandle in 1946. I have lived in three other states and one other country and Texas is the one I always come back to. And, yes, I do pledge my allegiance to thee Texas.

Great article. I wish I could write this way. Roger H.